Student projects from the AUAS – Minor Digital Media Strategy

In the last semester of 2022, students received an assignment to develop technology-based instruments that can support communities to share and manage their collective resources. The students’ work focused on the real-life community De Warren that has – after many years of development – recently settled in its collective residential building in IJburg, Amsterdam. The students were asked to consider the particular values and objectives of this cohousing community as well as the ensuing design dilemmas (i.e. the Design Canvas Dilemmas Digital Platforms for Resource Communities from the Circulate project) when creating their applications. This resulted in four apps in the domains of sharing food, spaces, mobility and “things”. These prototypes are separately presented below, including the reflections of both community members and observant researchers.

Sharing Food

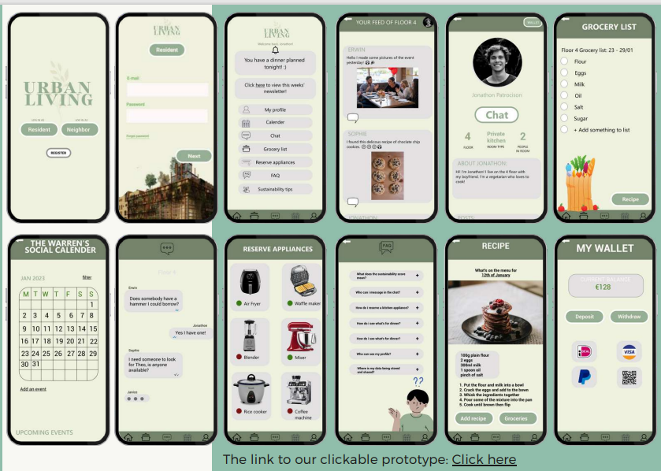

The Urban Living App

This application targets both cohousing residents and their neighbours in the broader area and aims to easily share meals and thus to stimulate social connections. It focuses on facilitating the process of planning meals, offering a shared calendar, shopping lists and recipes. The calendar shows the planned events (e.g. dinners) and members are able to indicate if they attend. When choosing to attend, the member sees the “chef” for that particular mealtime, the dishes that will be served as well as how long it has been since he/she joined a common meal. In addition, grocery lists, reserving kitchen appliances and notifications for allergens are offered.

The makers emphasize the social aspect of the app, specifically the chat function and the personal profiles. The prototype also contains a wallet function enabling to view and manage payments, transaction history in real time and check balance, linked to bank accounts and debit cards. Members’ accounts enable personal feeds such as posting recipes, pictures, short messages and sustainability tips, designed to be shared among residents on the same floor so that they can socialize, form connections and update one another.

The app makes the inclusion of neighbors possible. They can create an account that contains the chat function, personal profile, recipes, and a shared calendar showing events for the neighborhood. The makers of the app also provide a sustainability score system to increase residents’ awareness and to influence their attitudes and acts. It ranks members’ actions, choices, and lifestyles on a scale ranging between “poor” and “good”, based on data collected and analyzed through algorithms of the residents (e.g. eating or purchasing habits) and the building (lights, heating, electrical devices).

Reflections by the residential community De Warren

Residents appreciate the organizing potential of the app as the management of cohousing life is a complex task. Hence, this instrument is believed by the community as a very relevant, feasible and realizable one in view of the needs and the features of the app. It has a wallet function with a money-based feature, which intrigues the community, as it can help to fluently coordinate community issues. Furthermore, the consideration of personal preferences (e.g. allergies, vegetarianism, distaste) is valuable and therefore it would be useful to know if and how that can be attached to the recipes and the meals to be prepared. Another point of attention is the possibility of including household chores (cleaning, washing the dishes, shopping etc.) and the corresponding responsibilities by members in the platform. The app also raised the concern about dealing with last-minute cancellations and their adverse consequences (e.g. purchasing and preparing redundant food) – for instance, should there be a timeslot for signing up and annulling? This mirrors the dilemma of ‘’human versus algorithmic governance’’ because digitally encoded terms cannot be altered in unforeseen scenarios and need spontaneous human intervention. The human viewpoint also surfaces in the community’s intention to place a physical screen of the platform in a main common area so that it is available and noticeable for everyone in an offline mode.

Residents of De Warren are enthusiastic about the sustainability scoring on the app and wonder if and how this function can be applied for food waste management (like selection).

At the same time, the tracking and recording facets of the app do not make too much sense for the community as members do not intend to use a public monitoring – “we are just doing things together, we live there together, we do not want to put a coin to somebody’s hours and efforts, thus, no currency for time”. In connection with this, “we also do not wish to observe members’ recognition for each other’s’ cooking skills, that is too personal, so let’s not make a digital item of it”. This perspective refers to various design dilemmas at the same time. In terms of ‘’privacy vs. transparency’’ making information clearly visible for everyone helps members to see how the system as a whole works, who contributes to the community and/or to a sustainable world and in what ways, and who makes use of the common life. At the same time, residents wonder about the extent to which they wish to manifest their individual uses and contributions, worrying about privacy, internal comparison and ensuing rivalry. In terms of ‘’quantified vs. qualified’’ values measuring allows members to make the system and its dynamics noticeable as well as how (often) members use and contribute to the commons, which may also be utilized for recognition/rewards. Yet, the formal accounting of members’ actions can undermine the human/social character of the inner relationships in the community through competition and diminishing intrinsic motives prompting actions merely for recognition, good reputation or rewards. The dichotomy private vs. collective interests also relates to a cohousing community where on the one hand members are expected to constantly contribute to sustain the collective lifestyle. On the other hand, though members also have the right to control their time and agenda and to guard a healthy balance between common and private life.

Residents appreciate the app enabling them to include neighbours in community events since they ambition to reach out to their broader surroundings. At the same time, members wonder how they can genuinely include neighbours so that they actually join, which again draws attention to the tension between algorithmic and human governance: the technology-based enabling feature can only supplement social exchanges and real-life mobilization.

Reflections by researchers

The prototype induced the question whether keeping track of and recording members’ actions (for instance: who and how frequently joins common meals, cooks community dinner or cleans up the kitchen; sustainability scores and ranking) is possible and preferred. And, if monitoring is favored by members would they chose to make it public and visible by all cohousers? Or, would the recording system be used only to confidentially inform individual members without publicizing data towards the whole community? As mentioned above, this issue invokes the consideration of various dilemmas to be taken by the designer, namely, choosing between privacy and transparency, qualifying and quantifying values as well as private and collective interests. These design dilemmas also refer to the idea of incentivization in the sense of stimulating members to (more often) take part in joint events, to cook for the group or to assist in the common household, which may strengthen the sense of belonging and group cohesion or raising awareness of sustainable life choices. An incentivizing scheme can also draw on reputation, rewarding and sanctioning. Yet, such encouraging efforts may be experienced by members as a group pressure to make them behave and act in a certain – ‘’desired’’ – way, nearing manipulation and coercion.

Further questions touch upon the underlying governance system that the application does not make explicit. In this regard, researchers enquire about actors and decisions concerning, for instance, the events or the cook. Further issues raise concerning the functionality of the app and the objectives of the community: Can neighbors also borrow kitchen appliances? Will there be a bookkeeping scheme for borrowing items (e.g. from whom, by whom and what is borrowed and what return date is preferred). How will the community take care of the leftover food in the common fridge?

The sustainability ranking based on residents’ data also generates queries: does the design include all key consumption information including residents’ individual choices of food, travel and clothes, which might give a more precise calculation of their sustainability scores? If yes, the design should deliberate about people’ privacy in regard to exposing their personal preferences as well as the time needed for registering these data.

Finally, there are thoughts about the chat function of the app enabling to share recipes, pictures, messages and sustainability tips with the people on the same floor ‘’to socialize, form connections and give each other updates’’. What is the idea behind a floor-based group formation? Will it not pave the way to the rise of territory-based social cliques potentially offsetting community spirit?

Sharing Space

The Spazeshare App

The main aim of this digital platform is to facilitate residents to share their common spaces ‘’harmoniously’’ and ‘’easily’’. It includes a calendar with an overview of the planned events and their locations, for which residents can register. Residents can also create their own events in the calendar and make reservations (timeslots) for the various rooms in the building. Moreover, neighbours can be included who, after signing in, receive news regarding activities at De Warren. The profile feature of the app enables residents to place personal information including their participation in (community) activities. Spazeshare also offers a forum where members can interact with each other (e.g. questions, survey polls, discussions). A further feature of the tool is the digital key system accessible on smartphones, including one-time entry codes for neighbours, which is intended for easy access and privacy. This application is meant by its makers as the sole way to participate in and create activities and to enter common rooms. However, for less tech-savvy inhabitants a physical bulletin board will also be placed in a central common area.

Reflections by the residential community De Warren

Residents appreciate the professional approach that may help a much-needed efficient organization of cohousing, making this app applicable and very feasible in the eyes of residents. At the same time, the digital key system was seen as too commercial, going against the community mindset. Residents furthermore find the digital key quite complex, being indeed a shift towards efficiency and convenience as in a carsharing scheme though providing a much less personal, social and interactive management. This novel function would require a large transformation of their present infrastructure containing old-fashioned keys overall – so, they wonder if the app be coupled to their existing system? Such a digital lock scheme will for sure not be used in the coming ten years, residents say, so they would rather seek alternative possibilities. A further issue that causes concerns is the responsibility of cleaning the common spaces and how that can be involved in this tech-based platform. Such tasks, as the designers propose, are to be arranged based on trust and social control although residents of De Warren require that feedback might be provided through the app. This links to the dilemmas ‘’qualified vs. quantified values’’ and ‘’incentivization vs. manipulation’’ since formally recording and assessing members’ tasks and actions can offer useful and motivating insights while it can curtail trust, solidarity and generosity and can increase a sense of force. Residents also ponder, similarly to the previous prototype, on how they can induce neighbours to partake in common events organized by the Warren. This again mirrors the tension between human vs. algorithmic governance in that it highlights that technological enablers alone do not suffice for spurring relationships.

Reflections by researchers

The prototype raises questions about underlying governance issues like: ‘’who decides and how if someone from the neighbourhood intends to make an account?’’ or ‘How to attribute the spaces fairly (avoiding dominant use by the same members and hence internal fighting’’)?, and ‘’in case of scarcity is there a prioritizing mechanism for attributing rooms and based on what criteria?’’ (this is now facilitated by the discussion option in the reservation system, echoing the nature of the social sharing culture). Accordingly, makers and users might need to consider if procedures, power-sharing, decisions, control mechanisms, administration as well as roles (for instance, for neighbours) ought to be delineated and formalized. And, the potency of disputes as a result of shortage and urgency calls for anticipation in the form of steps and measures to resolve them, which touches upon the design dilemmas of private vs. collective interests, quantified vs. qualified values and human vs. algorithmic management. Furthermore, the profile feature of the app rouses the design dilemma of transparency vs. privacy: the tool publicly displays the activities and courses wherein a member participates, which can lead to pleasant exchanges, yet, it can also reveal aspects that the relevant person wishes to keep confidentially. Concerning the digital key, its necessity needs to be appraised by the residents from the perspective of personal, social mediation vis-à-vis computer-based intervention. It might also be solved by a concierge, by an open entrance or by the organizer of the activity temporarily taking care of the keys.

Sharing Mobility

The Sugremo App

This digital platform supports the sharing and management of mobility possibilities within De Warren community. It aims to help residents travel in a sustainable, efficient and cost-effective way, based on an app facilitating the sharing of various vehicles (e.g. car, boat, bike) that are jointly owned by the community. The app has a wide range of functions and screens though the main aspects consist of the booking system, a map for journey planning, chat/message function and the payment scheme. Sugremo seeks to draw residents’ attention to the sustainability dimension of their travel, using so-called ‘’greenward’’ elements. For instance, a tracking system registering personal statistics offers members a periodical overview of their CO2 emissions so that ‘’you can compare your annual usage and outperform yourself’’ or, when choosing among the vehicle options a notification pops up to remind the user about a more sustainable travel mode, and if relevant, a rewarding notice. The prototype also offers members the possibility to financially invest in community projects, which is rewarded by an individual message and, if favoured, by being rated in a reputation list.

Reflections by the residential community De Warren

Residents appreciate the overview functions such as the available mobility options (e.g. car, public transport, bike), vehicle reservation and payment. Also, the Spotify functionality seems residents a nice collective aspect that deserves further attention within the group. On the other hand, co-housers are overwhelmed by the too many functions of this – ‘’very ambitious’’ – application, wondering how to come to grips with all those elements as potential users. A further concern stirred by the prototype is the probable need of many data and algorithms to launch the system, especially the environmental and sustainability analysis – ‘’how to implement this at all?’’. All in all, this application was more of a disappointing surprise for De Warren residents as it does not mirror their needs and goals described beforehand. This app is ‘’not realizable, made too complicated, overstimulating the user by its many functionalities.’’ However, some of the sustainability dimensions of Sugremo appear the community to be quite applicable in their future scheme of mobility sharing based on the six cars owned but not frequently used by their individual fellow residents.

Reflections by researchers

The mobility app draws attention to the issue of scarcity and its management, namely, how the system distributes a limited amount of vehicles among the group members. So, is it a ‘’first come first served’’ system regardless of the level of need and urgency? Or, is prioritizing built into the system and if yes, based on which criteria? And who makes these decisions? A further main aspect of the prototype reveals the importance of considering the design dilemma about ‘’incentivisation versus manipulation’’ – that is, what is the threshold between a paternalistic, calculative group pressure and beneficial nudging concerning recurrent notices about public transport or the reputation scheme linked to members’ investment efforts? This latter also touches upon the dichotomy between quantifying versus qualifying activities, namely, the extent to which individual contributions need to be formally captured and circulated. The prototype also evokes queries about the tension between privacy and transparency, which concerns data sharing with third-party providers. Here, the question arises about the level and method of transparency toward the user -for instance, alerting users when their data are shared or users’ prior agreement to terms of use from third-party platforms. The privacy-transparency duality also refers to the booking system of the app since it necessitates the community to deliberate if members’ journey destinations should be widely visible and shared. A further thought provoked by the instrument is about involvement and omission, which also applies to the dilemmas ‘’quantified vs. qualified values’’ and ‘’human vs. algorithmic governance’’. This concerns members staying outside the Sugremo app due to lack of need and/or capability to use vehicles: are they supposed to join the system to show and get recognition for their exemplary behaviour? And will the green reward scheme be worth their efforts?

Sharing Things

The 2Share App

This app helps residents of De Warren to borrow personal items such as tools, kitchen appliances or clothes. Participants can upload items with pictures, descriptions and categorize them to offer an easy overview for fellow users. The app is rooted in the following basic principles: members’ willingness to share, equal responsibility for the items borrowed, a scheme easy to understand and to use as well as a fair way of sharing. It also has a chat system ‘’to maintain the human touch’’, through which residents can communicate and make arrangements. The app is furthermore intended for neighbours to promote and diversify sharing within the broader area. They can join and make use of all features with a QR code.

Reflections by the residential community De Warren

Residents love the simplicity and thus the doable facet of the prototype that they could quickly build up and start using. They are particularly enthusiastic about the specific item page displaying a clear overview at a glance. Similarly, the chat function is considered very useful. Yet, despite its aim to keep the human aspect in the exchanges, it may depersonalize transactions since it enables lending without too much conversation. Therefore, residents believe that adding further categories (e.g. ‘’please knock on my door’’; personal instructions are vital; requesting items back) might be valuable. Likewise, co-housers will need more generic buttons and an administrative outline displaying all items loaned out. Residents also wonder if the items may be linked to specific persons, for instance by using a QR code, so that direct contact can be taken for further questions and details. Although Warreners sympathize with the workable facet of the app they find it less relevant for the community at this moment. Also, they believe that they can arrange this function by themselves, actually they already manage this type of sharing through WhatsApp. Yet, residents point to the interesting potential of this app for evolving into a platform for sharing things with the neighbourhood.

Reflections by researchers

The first observations relate to additional functionalities and community objectives: Can people also upload their quest for items? Is the app about borrowing, renting or second-hand purchases? Does it allow sharing in two ways, namely items between individual residents but also ones that are owned collectively? Further remarks concern the user-attentive character of the application featuring maybe too many smart and sophisticated components. This on the one hand relates to residents’ specific wishes (e.g. indicating the level of risk to borrow something, option for personal talk, an overview of borrowed items), which are not entirely fulfilled by the tool. On the other hand, it also concerns the feasibility of the prototype launched in a real-life situation, for instance, one wonders if residents have sufficient time and energy to take professional photos of their numerous loan items. This might be solved by a more motivating strategy, namely, flipping the taking and the sharing, so that lenders take the photos. Finally, the makers and users can consider further features to regulate communication modes, so that it allows efficient and rapid transactions but also contains a built-in interval to stimulate more personal interactions. This bears upon the design dilemma concerning quantified versus qualified values in a resource community.

Conclusions

Reflections from both the community (users) and researchers show that the design of technological applications for managing communal resources need to go beyond the mere consideration of user functions, their outward appearance and state-of-the-art capacities. This became manifest by the numerous questions emerging given the steering mechanisms underlying the prototypes, such as: Who decides about the app features and requirements or in specific (exception) cases? What are the criteria for tech-based choices and by whom? What properties of conflict resolution can be added to these apps and how to define them? How can the existing power-sharing structure of the community be embedded in the applications?

These questions mirror the general impression of the Warren community, namely, that the technological tools were constructed rather schematically whereby the consideration of real-life situations was not always taken into account. For instance, a recurrent concern is the tackling of scarcity across all domains (e.g. insufficient capacity of vehicles or spaces for the number of requesters) and if this should be addressed by the ‘first comes first served’ principle or by an alternative procedure. This concern was accompanied by further queries, remarks and worries about the app arrangements, which illuminated important design dilemmas recurring in the various sharing domains. These dilemmas were raised by the contradictions between the particular values fostered by De Warren and the app functionalities proposed. These issues of unease were particularly triggered by the outspoken perspective of the Warren co-housers to ‘maintain the human dimension’’ and thus to avoid any kind of record tracking and scoring system: ‘’we do not want to call each other to account or to reward members on the basis of data (monitoring), we find that crooked.’’ As such, the Warren members wish to observe and signal issues in the community in a more instinctive way, paying human attention to understand the behaviour of their fellow members. Herein, face-to-face relations form the core of their guiding principle. An additional element of the ‘’Warren mindset’’, which became apparent throughout the assignment is refraining from commercial, market-driven attitudes. Accordingly, members’ concerns on the design features relate to various pressures such as the gap between efficient, rapid (digital) transactions versus ‘’slow’’ social/personal interactions or measuring, monitoring, scoring and quantifying actions versus confidence in the beneficial contribution and responsibility by all members of the Warren. They furthermore also refer to tensions between private versus collective interests as well as between transparency, data handling by third parties and residents’ confidentiality. And, while incentivization and stimulation of members’ participation is an urgent subject for the Warren -like for most cohousing communities- they seek how to accommodate it in a suitable way in a digital platform, avoiding scoring, rating, rewarding and comparing individual members. These ambitions underline yet again the significance of taking the particular wishes of a community into account when modelling digital instruments, even against the huge temptation of the newest and most advanced tools out on the market.

The assumptions of the designers seemed to play a critical role in shaping the end products. One assumption persistently expressed by the students relates to the harmonious co-existence in housing commons at all times, which explains why the applications proposed do not offer functions for coping with disputes, and unusual or unexpected scenarios that in real being often occur. A further essential assumption can be exemplified by the designers’ outright belief in the enabling potential of technologies and thus their easy-going tossing around smart appliances and ensuing practices. This ’if you build it they will come’ approach is very noticeable with regard to including the neighbourhood in common activities, namely, the belief that extending app functions to the wider environment will inevitably make other citizens participate. This purpose, however, in reality, would require commoners to engage in ongoing offline efforts and personal exchanges with people living nearby, which cannot be substituted but merely complemented by digital applications.

The abovementioned issues, shortages and queries display that the system behind the system, that is, the governance scheme underlying communal life and sharing, reflecting reality and the specific needs of the community requires attention and elaboration when designing digital infrastructures for resource communities. Also, the operation of power and conflict in particular resource-use scenes needs to be well understood in light of the specific values of the community. Since these values are the fundaments for establishing governance mechanisms for resource-managing applications their articulation lends itself as the first step in such design processes. This has prompted a further issue in the work sessions, namely, the responsibility of the designer: does the designer take the role of structuring the discussion in the community or does he/she stop at a point, leaving it up to the community?